As a medical social worker in a trauma unit, I was frequently in situations where a family was being informed that their loved one had passed away or was passing away. I witnessed an extraordinary spectrum of ways that people had — or had not — developed a relationship with the archetype of death.

For the most part in American culture, it seems that we are so defended against the certitude of death, so frightened by the cessation of life, that we are often philosophically unprepared to imagine who we would need to be in order to gracefully slip into the hands of the death mother when the time is just right, to welcome the mercy of being liberated from our suffering. We make it more difficult, more painful, more frightening, more alien than perhaps it would need to be.

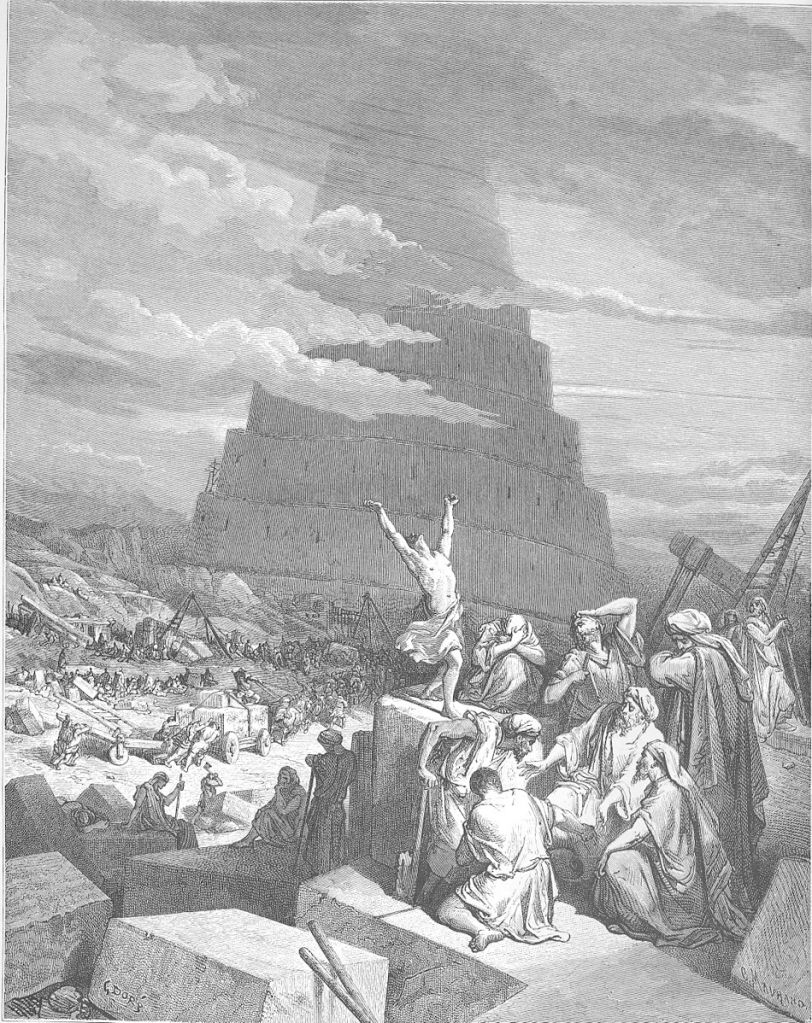

Certainly, we deprive ourselves of the elegant religious aesthetic that more ancient cultures had been able to cultivate. This was due in part because, lacking the technology we have in the modern age, they could not forestall death. Therefore, developing an attitude of acceptance of death was essential.

But also it seems that death was considered an intrinsic and essential part of life. Part of the religious shaping around death was the certitude that the ancestors continued to be in intimate relationship with their progeny, facilitating, protecting, helping, nurturing. The way we have adopted a scientific attitude in the modern era has deprived us of some of the essential aesthetic that the ancient world had around death.

Of course, embracing science and a scientific attitude has given us a great amount of benefits, but when facing existential realities like death, we have actually been deprived of the help we might have had. We insist on consciousness as the sole reality, we insist on cognition, we insist on science. But by its very nature, death is beyond our ability to think through or cognize.

This is where the realities of the unconscious can come into play, where we turn to mythology, we turn to images from religion, we turn to dreams, we turn to psychic life. But in our modern day world we tend to be so concrete, and so insistent on consciousness as the arbiter of reality, it makes something like death very foreign and alien.

from Stewart, D., Marchiano, L., & Lee, J. (2022, June 10). Episode 217 – Death: A Jungian perspective. This Jungian Life.

Without an understanding of myth, without an understanding of the relationship between destruction and creation, death and rebirth, the individual suffers the mysteries of life as meaningless mayhem alone.

Marion Woodman