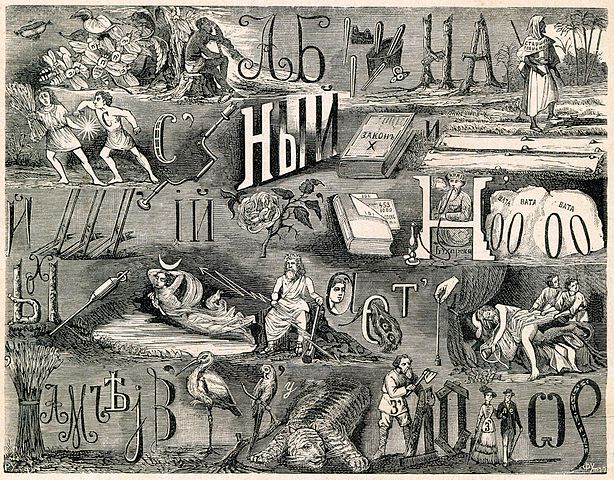

“The hybrid blends of thought, feeling, and perception that are the subject of this book are metaphorical expressions of the psychotic person’s mental life. Psychotic symptoms are like a rebus that tells a story with words and images. The word “rebus” comes from the Latin phrase, non verbis, sed rebus, meaning, “not by words, but by things.” A familiar rebus contained in books for young children alternates a picture of a cow with the word “cow” in the narrative of the story.

“Hallucinations, delusions, and other anomalous subjective experiences that occur in psychosis are a special sort of rebus in which an image linked to words is pressed not into print on paper, but rather into the canvas of surrounding reality in what Marcus has called “thing presentations of mental life” (Marcus, 2017). Psychotic persons communicate in words, verbal metaphors, and images composed of altered perceptions of the outside world. Collages of images, words, and hybrid subjective states coalesce to form psychotic symptoms.

“A psychotic symptom may be the patient’s good-faith description of an anomalous state of mind or a sort of puzzle of the heart to be solved by the patient and therapist, with an emotional code to be deciphered. In some cases, the metaphorical meaning of the psychotic symptom is easily understood. In other instances, the meaning is obscured by altered self-states, or hidden by particularly idiosyncratic symbols and the scars of many years of traumatic living. The psychotic person in effect hides psychological pain in plain sight within the metaphorical meaning of the psychotic symptoms.

“The psychodynamic interpretation of a psychotic symptom invites the patient to express the metaphorical meaning of the symptom in words, connected with painful emotions, associated with adverse life experiences, a process that brings split-off elements of mental life back into conscious awareness, where they can be processed to foster emotional growth and recovery.”

— from Garrett, M. (2019). Psychotherapy for psychosis: Integrating cognitive-behavioral and psychodynamic treatment (1st ed.). Guilford Publications.

Marcus, E. (2017). Psychosis and near psychosis: ego function, symbol structure, treatment (3rd ed.). Routledge.